"I am more than HIV" - Pete's second spring

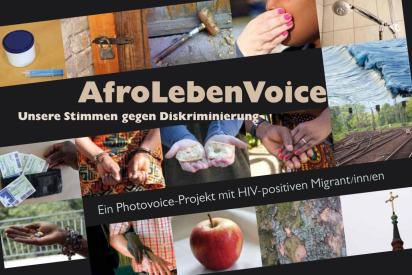

In the AfroLebenVoice project, HIV-positive migrants took photos of their lives, told each other the stories "behind" these photos and, as a group, found out what they have in common and what needs to change. By Julian Vetten

Pete's smile is terribly infectious. It starts with her sparkling ice-blue eyes, moves on to her countless laugh lines and ends with the corners of her mouth raised wide to reveal snow-white teeth. "I've been very happy since I've been here," says Pete (name changed, editor's note), followed by a sentence that doesn't seem to fit the context at first glance: "I've met so many great people - and I don't know if I'd be so lucky if I didn't have HIV." There it is again, that inimitable smile - it's the only thing about Pete that's infectious.

The 33-year-old has known about her illness for almost ten years - and thanks to modern treatment methods, she can now lead a largely symptom-free life. If Pete regularly takes the combination preparations required for her retroviral therapy, the so-called viral load is permanently below the detection limit. Theoretically, she could even have unprotected sex with her healthy husband. So everything is fine? Not at all, because in addition to her HIV infection, Pete has a completely different "problem": she is not from Germany.

"Although times have changed, it still happens often enough that an HIV diagnosis alone leads to exclusion," says Tanja Gangarova, migration officer at Deutsche Aids-Hilfe. "However, people like Pete face a much bigger problem: HIV-positive migrants not only experience stigmatization due to their HIV status, racism, Islamophobia, xenophobia and structural discrimination, i.e. inadequate access to the healthcare system in Germany, the labour market and education, also play a role. This is known as the phenomenon of multiple stigmatization." Pete had to experience this first-hand - and although the little woman with the irrepressible energy has largely shaken off such problems and could look to the future, she is doing everything she can to break down the barriers for those who follow her. A look into her difficult past helps her to understand.

"I have always dreamed of more rights"

The change that Pete undergoes when she tries to talk about "her homeland" is clearly tangible: The "eternal waterfall of words", as she jokingly calls her need to communicate, gradually dries up - and the lively glare disappears from her otherwise intense eyes. "I come from a country where human rights are not respected and I grew up in a male-dominated culture," she bursts out. "I've always dreamed of more rights, of freedom..."

Even in comparatively tolerant Algeria, where Pete is studying literary history and giving birth to her first child, she cannot live without fear. "As a single mother with concrete ideas about life, you don't stand a chance in the Islamic world," she says and finally draws the consequences: Germany was to become her new home. "I wanted to go where my rights as a woman were recognized. My dream was that I wouldn't immediately be pigeonholed. I was prepared to accept any restrictions for that."

And there are plenty of restrictions in her new adopted country: instead of being able to build a new life in Germany, Pete is condemned to inactivity in a "Central Initial Reception Center" while waiting for her application for asylum to be accepted - three long years.

The stomach problems that Pete had been struggling with for some time worsened in the initial reception center. Apart from fruit, the then 23-year-old can hardly keep anything down, but the home only serves apples - to this day, her former favorite fruit makes her stomach turn. Pete only received medical care when her condition deteriorated to such an extent that there was no way around an operation. Her four-year-old son has to go to an orphanage for the duration of her stay in hospital, and the completely distraught woman herself is forced to sign a jumble of papers during the preliminary examination, which she does not understand and cannot even get in English when asked. Among them is a declaration of consent for an HIV test.

"A single poster can save lives"

"Positive," is the doctor's succinct verdict. Not a word of regret, no advice, no psychological support. Just a note that the originally planned operation would take place in ten days. It's hard to imagine the personal hell Pete must have gone through in those ten days, only one thing is certain: "I thought about suicide, and not just once." But she decides to carry on - even if it is only for her son.

"It's enough if someone reaches out their hand to help you out of the hole. The rest will work itself out," says Pete, ten years her junior. In her case, the helping hand is a young junior doctor who happened to notice how the young woman had been dumped by his colleague and researched offers of help on his own initiative. Because there were no comparable services for migrants at the time, he sent Pete to a gay counseling service - better than nothing, after all. The young woman discovers the second helping hand in the form of a telephone number on a campaign poster from the Federal Center for Health Education (BZgA): "A single poster can save lives," she says today.

From then on, things improved for Pete: the therapy worked well and she was soon physically better. The support services gave her new courage to face life - and when she finally met her current husband, Pete experienced a second spring. "I really wanted to have a second child. When the doctors gave me the green light, I knew: if something like this is possible, anything is possible."

In the years that followed, Pete freed herself from the role of passive recipient of help and got involved wherever she could. Whether as a spokesperson for a self-help group, cooking with other HIV-positive people in the "World Kitchen" or as an actress in the "Mobile Enlightenment Theater": "I want to open a window for people into another world that is not so different."

"Everyone has something to offer"

Pete's latest project, which she has realized together with other HIV-positive migrants over the past two years, shows just how accurate the picture she paints is: "AfroLebenVoice - Our voices against discrimination" impressively demonstrates the different feelings that each person has about supposedly familiar concepts. On each double page of the photo book there is a picture with a corresponding text, in Pete's case it is the apple mentioned above: round, crunchy and delicious is how most of us would describe it in the photo. Pete, on the other hand, writes after her experiences in the initial reception center: "Today I have a not entirely secure, but better residence status and can now afford apples. But I can no longer eat them - they leave me with a bitter aftertaste."

It is precisely these breaks in the common perception that get under your skin - and in the other direction too. "We wanted to show diversity: Every sad story is followed by an encouraging one," said Pete. In her case, this is a picture painted by her youngest son. "I've always wondered if I'm a good mother, if my children are happy. A few days ago, my son came to me and said, 'Mom, I love you so much, you're the best mom in the world. You are so good to us that I want to copy you, so other children can have such a great mother too That's the best compliment a mother can get!"

The photo book, initiated and supported by a special project of Deutsche Aids-Hilfe, has long since become a self-runner. "The book has created a spirit of optimism in the community. Some of us have experienced for the first time in our lives that everyone has something to offer." Few people know this better than Vieux, one of Pete's fellow campaigners: "I am only a 'tolerated' person and have hardly any rights here in Germany... But I was needed (for the project) and that makes a big difference!"

Vieux and Pete sum up what Tanja Gangarova had hoped for in the run-up to the project: "Through the AfroLebenVoice project, we wanted to stimulate transformation processes on two levels: Within the group, it was important to us to facilitate a respectful and constructive exchange among ourselves on the topic of discrimination and sources of strength. We wanted to activate and strengthen the resources, skills and knowledge of those involved. And externally, we want to use the project results to sensitize the general public to the realities of the participants' lives and thus contribute to reducing discrimination against migrants in Germany."

Pete's eyes light up when she talks about her group's plans: "Maybe one day we'll make it into politics with our projects." The goals that Pete and the other participants in the PhotoVoice project have set themselves may seem unattainable at first glance - but the greatest realization has long been a certainty for her: "I am more than HIV," says Pete, smiling her terribly infectious smile again - and speaking not only for herself, but for all HIV-positive migrants in Germany.

Downloads

-

Photo book AfroLebenVoice (1.59 MB)

A photo book that was created together as a result of the AfroLebenVoice project